Cyber risk is a growing threat to organizations of all shapes and sizes. Cyber risk quantification allows organizations to better understand the financial impact that these risks pose; however, setting the scope of quantification activities and clearly articulating their outputs can be a challenge. Recently, Protiviti teamed up with the FAIR Institute to review how organizations can implement key Factor Analysis of Information Risk (FAIR) concepts, such as where FAIR fits into the larger risk management landscape and how organizations can right-size their assessment scope by establishing a quantified risk baseline. This blog reviews Protiviti’s baseline cycle concept, which is an iterative approach to identifying, quantifying, and tracking the risks that matter to an organization.

What is a baseline?

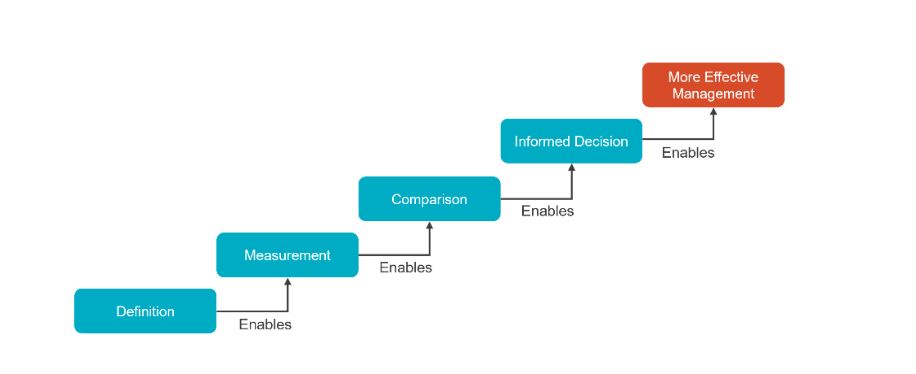

The risk management stack describes the dependencies underlying common risk management capabilities. Organizations seeking to effectively manage risk must first be able to define and measure it, as these capabilities are prerequisites for risk comparison and related decision-making.

Organizations often struggle to clearly define and consistently measure risks. These problems are especially apparent in cases where risk quantification is employed; in a massive universe of potential threats, actors, and impacts, it is critical to focus efforts on the risks that matter most to the organization. Clearly scoping a risk baseline addresses this and other common issues organizations encounter when beginning to quantify risks.

A risk baseline is a methodically defined and consistently maintained aggregate view of risk scenarios across a given risk domain (cyber, operational, etc.)

Establishing a baseline of quantified and ranked risk scenarios:

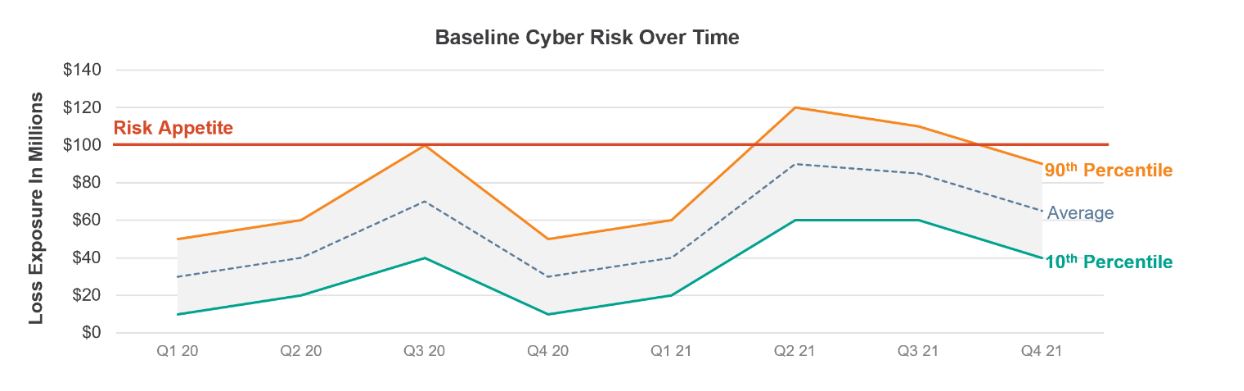

- Establishes a reference point for evaluating a changing risk environment over time

- Delivers quantified, dollar-value estimates of loss exposure

- Enables tracking risk exposure against an organization’s stated risk appetites

- Provides a ready-made scope for reassessing risk in the future

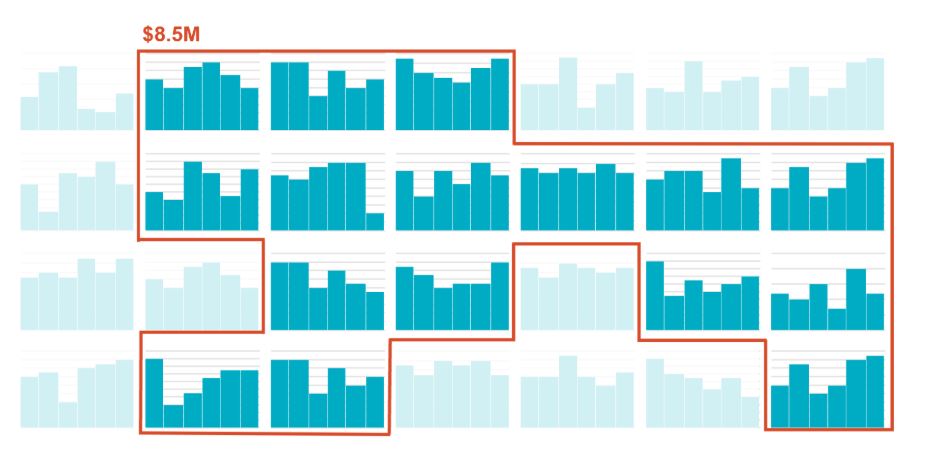

The below graphic demonstrates a typical output from a well-maintained risk baseline. In this example, an organization can trend its dollar-value cyber risk over time and track it against a defined risk appetite.

Developing a quantified risk baseline

Establish scope

Baselining starts with defining the risk domain’s scope and documenting it. While subsequent steps are cyclical, scoping ideally happens only once. Carefully articulating what types of risks fall into a given domain avoids “what about this?”-type questions down the line. For example, are non-malicious outages a cyber risk or an operational risk? What if they stem from the failure of an external actor, like a key service provider—would that then be considered a third-party risk? Domains should align to an organization’s existing risk classification scheme. Absent formal policy in this area, the scoping phase of the baseline process is when these classifications should be made.

Establish risk scenarios

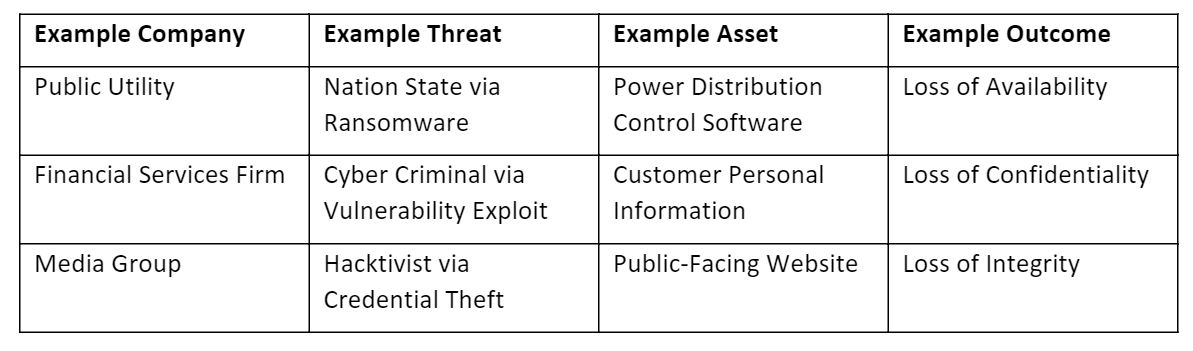

Next, practitioners establish risk scenarios. These scenarios are typically the aggregate output of threat and asset discovery processes, which seek to identify:

- Assets of business value. In FAIR, these are typically repositories of critical data, revenue-generating systems or processes, or other entities for which disclosure or unavailability may lead to material financial impacts.

- A threat is an actor capable of causing a loss to the asset. Threats are typically described by actor (e.g., Cyber Criminal, Nation State) and method (e.g., web app exploit, ransomware). Threat discovery typically leans on industry analyses (such as Verizon’s Data Breach Investigations Report (DBIR)) or organization-specific threat intelligence.

- An impact describes the effect that an asset’s loss or damage would have on the organization. For example, an asset could be disclosed (confidentiality), become unavailable (availability) or be illicitly modified (integrity).

Risk management practitioners identify potential threats against each asset and state the threats’ impacts to create scenarios. Risk practitioners should focus efforts on identifying key data inputs during this step to ensure easy repeatability of these analyses in the future. These scenarios are then analyzed using the FAIR methodology and the results are cataloged. This collection constitutes a risk register.

Triage risks

Not all risks are equally probable, and only some are worthy of further attention. The goal of the next step – triaging risk scenarios – is to draw a line around the scenarios that matter most (see image below). Here, low-likelihood and low-impact risks are deselected so teams can focus on the risks likely to cover most of the critical assets and incidents resulting in financial and operational business impact. By approaching this deselection in an objective, quantitative way, practitioners express the expected coverage of the baseline as a subset of all identified risk.

Triage will deliver a prioritized set of risks that will be further reviewed for reporting and tracking purposes.

Quantify risks

The final step in creating a risk baseline is quantifying the risks identified and narrowed through the triage process (see Section 3). The result of this process is then a refined set of potential business and financial impacts, which include estimating loss exposure values that can be aggregated and reported as the domain’s quantified risk baseline.

Rinse and repeat

The creation of the initial risk baseline delivers a comparable and holistic view of a given risk domain in the organization (see Section 1), which will immediately empower decision-makers in their actions to manage cyber threats and business risks. Additionally, after this initial baseline is established, the organization will recognize additional benefits by periodically repeating the baselining process. Organizations can use baseline cycling to assess how risk scenarios change in aggregate from one period to the next (e.g., annually). In baseline cycling, practitioners repeat baselining periodically, taking the same steps with equal rigor, but with far less effort than the initial iteration. They evaluate new assets in the environment to add to the baseline and descope divested and retired assets. As an added benefit, baseline cycling creates dedicated time to refresh organizational knowledge of threats on a periodic basis.

Final thoughts

The establishment of a risk baseline is a powerful tool that provides organizations a defensible understanding of their risk in financial terms that will be tracked and maintained over time. However, proper governance is critically important in order to maintain meaningful baseline and cycling practices. Leaders and practitioners will want to document the procedures they undertake with each baseline cycle and commit to a cadence appropriate to their organization. They’ll also want to formalize a review process for revising any baseline’s scope. Holding baseline processes to standards in this way safeguards the reputability and consistency that make baselines and baseline cycling such impactful practices for managing risk.

To learn more about using FAIR for cyber risk quantification, contact us.